Problems are objects

The philosophical lesson of Theoretical Computer Science

Theoretical computer science teaches us something that I think is deep, philosophical, and often goes unnoticed.

The introduction to theoretical computer science I received as an undergrad taught me this: problems can be considered to be things. Problems have positive content and structure: there is an inner logic to problems. Problems have objectivity.

Normally, we don’t think of problems as things. Problems are the enemy of objectivity. To use a common metaphor, problems get in the way of things. Problems signify a lack– a lack in our understanding. If something is problematic, that means we can’t currently find answer. If we are consistently wrong, this is do to us: we are doing something wrong, or are unable to understand. Problems are our subjectivity clouding our vision of real, objective things.

But theoretical computer science, or rather, the move it makes, flips this on its head. If we are consistently failing to find a wrong answer, this might not be a failure in us, it might be due to the problem itself. We can study the problem to see how easy or hard it is to solve. Problems and their corresponding solutions are structured.

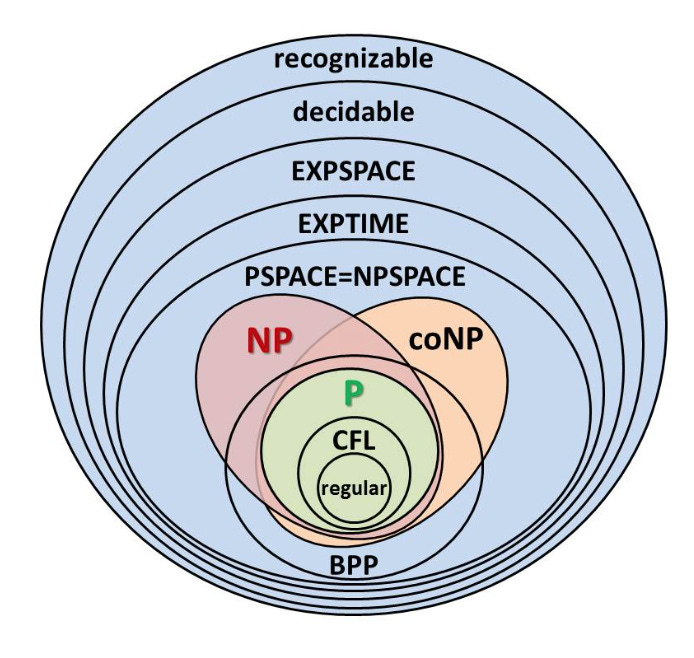

How do they do this? Well, if you look at one sub-discipline of theoretical computer science, you will see that they have mathematically classified problems into a hierarchy based on how complex they are– meaning, how much memory and time they take to solve. In the hierarchy, there are problems that can be solved in polynomial time, P, non-polynomial time, NP, and exponential time, EXPTIME. At least at the introductory level, P is taught as the class of problems that are “easy.” They can classify problems because problems can mathematically be “equivalent” to or “reduced” to other problems– it appears, that, many difficult problems can be reduced to an a logic-problem called “SAT,” which all “NP” problems are “equivalent” to. And so, if we can solve this one logic-problem efficiently, we will, overnight, have solution to a lot of very different problems. Notably, theoretical computer scientists have not proven– and might never prove– whether P and NP are equivalent–which, at least at the introductory level, is taken to mean that we do not know whether it is true that if we have a efficient way of verifying a solution to a problem, then we then can have a efficient way of finding a solution. For a much better introduction, watch this video:

.

Most astonishingly to me, even though I struggled to get my head around this in class, there is an algebra to problems.

This discipline of theoretical computer science that I described is called computational complexity theory. Computational complexity theory looks like it is asking empirical questions: “can we solve this problem feasibly? how fast can you solve this problem? “ But it is actually asking a purely formal, mathematical question, as it is looking at the constraints a problem’s structure places on hardware in general. Another discipline of theoretical computer science, computability theory, looks at whether a problem can be solved at all. Here, computer science coincides with metalogic, and all of the philosophical questions about the limits of logic are raised here, but in a way where you can see its practical implications, because what they are studying are problems.

Now, computer science analysis only works on well-defined problems, which have a yes or no answer. It is true that most problems are vague and ill defined, and anyone who has had the experience of having a ill-defined problem, anxiety, knows that we have no algorithm or clear-cut solution to the problems that anxiety comes along with. This raises interesting philosophical questions, which might be taken to point against thinking like computer scientists, but right now we are concerned with what computer scientists should teach us, not where they can be taken to an extreme. We will return to this, as this helps us explain why theoretical computer science does not subsume philosophy into itself.

The move that theoretical computer science makes should be taken by more people, especially philosophers. More people should think that problems are positive things, and that problems have structure.

For the first philosophical expression of the move that computer science makes, I think we should look to Kant. Kant, I think, was the first person to think in this way. He showed a problem: one could simultaneously prove that God does and that God does not exist, and that the world is both infinite and finite. But rather than thinking that this was a problem with him, he thought it was a problem within reason itself. He called these problems that live within reason “antinomies.” His solution to his antinomies very generally speaking, was to tell us to refrain from thinking about what the world really is, because we had run up against some sort of limit of what pure reason can think.

Hegel took the “problems are real” move further, maybe too far. Hegel did not go for Kant’s moderate solution of witholding judgement. Instead, Hegel notoriously thought that contradiction exists within the world. One way of thinking about this, is that the world gives rise to problems within itself. Problems are real part of the features of the world. Animals, in order to exist, often have to kill other animals. Thoughts, in order to exist, had to refute other thoughts. Animals don’t vanish into nothingness when they die, but rather decompose, create more living things and more problems for other the living things around them. Similarly, problems don’t vanish into nothingness when they are absolved, but rather create more things and more problems for things. The world is a problem-generator, and certain things (like life and thought) need problems in order to exist.

One might rephrase: the world is a sort of conversation, that poses problems for itself, and then tries to resolve itself. (Conversation makes more sense than his word “dialectic,” which has been mystified into meaninglessness)

One could radicalize this and take it to its logical conclusion. One might think that the only thing that really is, is problems. As far as I understand him, Deleuze thought something like this.

It seems to me that, analytic philosophy, though it has many virtues, and in many ways is the clear, logical, computational way of doing philosophy, has very ironically missed this insight. Philosophical problems are these things to tackle and solve, and then assert that your solution is the correct one above all others– things to take “views on.” We aim to solve them. Once they are solved, (if they ever are….) they vanish, and we can forget that they existed. Problems exist in order to eventually not exist.

Philosophical problems, on this view, have no positive content: they are merely a lack of knowledge on our part. A massive lack of knowledge on our part. The history of philosophy consists of philosophical problems kicking us in the ass.

Philosophy consists of tiring away, again at again, at solving problems that always get the best of us.

Realizing that problems have structure can help us take more healthy attitude towards philosophical problems, which can also help us teach philosophy better. You will probably not be the person to definitively solve the mind-body problem, the problem of induction, the hard problem of consciousness, or any other hard philosophical problem. But these are all interesting problems that live within reason, that have their own logic of plausible solutions and counters to those solutions. You can teach these problems that live within reason, and have teach people to trace the logical paths that structure this problem, and sometimes, you can find a new logical path. Philosophy teaches us to trace these paths in conversation.

And this is exactly what computer science teaches us. Computer science teaches us to think of the set of all possible solutions as a space, and finding solutions as searching that space. We look for paths to new solutions, sometimes getting lost, sometimes finding efficient solutions.

Philosophy, under this conception then, is exploring the space of the problem– the problem, notably, being inherently ill-defined– and all of the sub-problems that getting lost in the problem generates.

I think this is a great way to approach things. Others I know who are excited about CS theory in this way often get particularly excited about Jean-Yves Girard, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Yves_Girard

Analytic philosophy’s mistake is in trying to solve one problem at a time. What it should be doing is gathering up all the problems and seeing what they have in common. Problems have a structure, as you point out, but they also have a common source (as Kant vaguely recognized). Find the source and you’ve solved them all.